Last week, the Kenya Conference of Catholic Bishops (KCCB) issued the latest periodic statements on the nation’s State.

The statement, ‘Cry of the Oppressed’, voiced concerns on several issues affecting the country. Crucially, the bishops raised doubts about what they viewed as the State’s deliberate move to degrade faith-based organizations’ complementary role in service delivery, especially in healthcare and education.

They singled out some education-related bills that they argue dilute the church’s role in managing the learning institutions it sponsors.

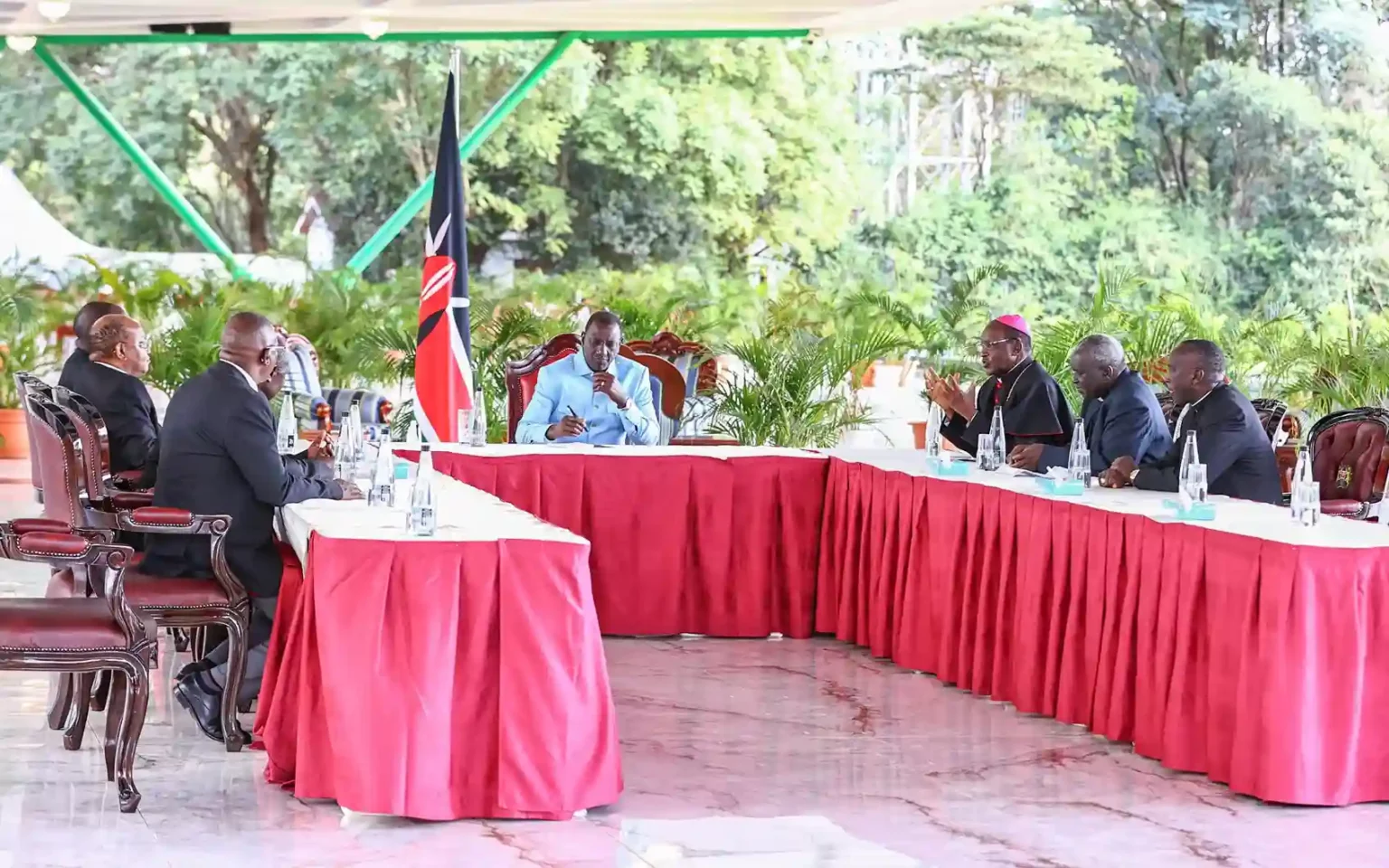

Hardly a day after issuing the statement, President Ruto met with the bishops, reassuring the church of the government’s commitment to continue the historic collaboration.

The KCCB’s statement is not isolated. Various faith-based entities have voiced concerns since Kenya Kwanza rose to power.

The unbearable cost of living, corruption, and unfulfilled promises made during the 2022 elections have been of particular concern.

Recently, the focus has been on the persistent insecurity affecting the North Rift and the ongoing doctors’ strike.

The swift move by the President last week to meet the Catholic bishops hardly a day after the latter issued a scathing statement against the government demonstrates the potency of the religious community in shaping and influencing governance.

It is important to underscore this point because of the palpable challenges faced by other actors responsible for holding state and non-state governments accountable. State entities include Parliament, the judiciary, and independent commissions.

Non-state entities include the media, civil society organizations (CSOs), trade unions, professional organizations, academia, think tanks, and FBOs. These entities are facing significant challenges, making the role of the religious community even more urgent and essential.

There is hardly any doubt that Parliament’s effectiveness is disappointingly degraded. It has repurposed itself as a tool for the executive’s convenience, literally servicing the president’s desires virtually unquestionably.

The judiciary’s quest to stand up to the executive has been met with predictable hostility by the latter.

The start of this year has been mainly testing for the two branches, with the President leading a sustained onslaught against what he claimed to be deliberate sabotage by the Judiciary. The less said about the independent commissions, the better.

The ecosystem has been similar for non-state watchdogs. Various tactics have, for instance, been unleashed to emasculate the media. A favourite has been the withdrawal of government-sponsored media advertisements to deny revenues to hostile outlets.

CSOs have not been spared either. In September last year, the government issued a directive requiring all non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and public benefits organizations (PBOs) to align their priorities with the government’s Bottom-Up Economic Transformation Agenda (BETA). It is no secret that CSOs need help to recapture their old shine.

The labour movement is limping, hardly able to shout amidst the impact of some government policies on workers. It is mainly seen as ingratiating itself with the current administration.

The system appears keen to render ineffective mechanisms of accountability and checks. Inviting the faith-based sector to rise to the occasion and slow down the trend is tempting. The call is not baseless.

Years ago, faith-based actors stood out as an effective countervailing force against the excesses of the regime of the day, especially at the height of a single-party dictatorship. This legacy of pride and responsibility can, and indeed should, be rekindled.

Secondly, religion played a key role in the last elections. Never before has religion been so extensively used as a tool of political mobilization.

Having been unleashed as a building block of the current administration’s rise to power, the faith-based community can repurpose itself as its Achilles heel.

As a key component of its makeup, sustained dissent by faith-based actors can easily discredit the regime and shake its foundation.

It is not immune to countermovements by the regime itself, though. Despite some obvious vulnerabilities, including those touching its revenue streams, the faith-based community can and should fill the palpable void.